3 Things You Should Know about Genesis

Most modern readers do not view Genesis as a carefully composed work of literature. We have become accustomed to reading it piecemeal. The public and private reading habits of Christians mitigate against the idea that Genesis should be understood as a single, coherent book. As a result, important aspects are missed. Let me mention three significant features of Genesis that need to be observed.

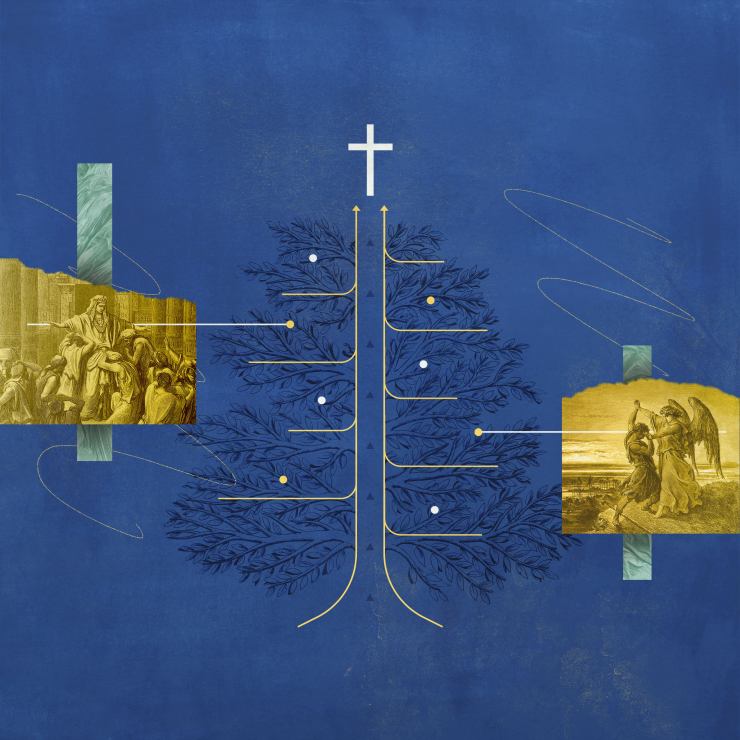

1. Genesis was composed to trace the history of a unique family line.

First, Genesis was composed to trace the history of a unique family line that highlights one male member in each generation (a “patriline”). The Greek term genesis means “genealogy.” This patriline begins with Adam and runs via his third son, Seth, to Noah (see Gen. 5:1–32). From Noah, the patriline is traced via Shem to Abraham (Gen. 11:10–26). Thereafter, the pace of the story slows, but interest in the unique family line continues. The childlessness of Sarah is a major barrier to its continuation, but God enables Sarah to have a son, Isaac. Beyond Isaac, the patriline is traced to Jacob (later renamed Israel), the younger twin brother of Esau. Esau should have been next in the patriline, but he despises his birthright and sells it to his younger brother, Jacob—who desires to be part of the patriline—for a bowl of stew (Gen. 25:29–34). Beyond Jacob, the patriline is associated with Joseph (see 1 Chron. 5:1–2) and his younger son, Ephraim, whom Jacob places ahead of his older brother, Manasseh (Gen. 48:13–20). Interestingly, Genesis often gives clues as to why firstborn sons are passed over in the patriline (e.g., Ruben’s inappropriate liaison with Bilhah; see Gen. 35:22).

While Joseph enjoys priority over his older brothers, Genesis introduces an important twist in the history of the patriline. In Genesis 38, a passage that is often dismissed as interrupting the story of Joseph’s life, attention is drawn to Judah. Read with an eye to the patriline, Genesis 38 is about tracing the line of Judah, which appears in danger when his eldest sons are struck dead by God. Tamar’s unusual intervention brings about a radical transformation in Judah’s life and results in the birth of twins. At this birth, once more the principle of primogeniture (the eldest son’s right of inheritance) is reversed as Perez breaks out in front of Zerah. Later, Jacob will pronounce a blessing on Judah that suggests kingship will be associated with his descendants (Gen. 49:8–12). This blessing is seen centuries later in the time of Samuel (see Ps. 78:67–72).

Why is this patriline so important? Beginning in Genesis 3:15, it is presented as leading to a future offspring of Eve who will overthrow the serpent, God’s archenemy. As Genesis unfolds, we discover that this promised offspring will be a king who will mediate God’s blessing to the nations of the earth and, as God’s perfect vicegerent, will establish God’s kingdom. With these expectations, Genesis looks forward to the coming of Jesus Christ.

2. God establishes an eternal covenant with Abraham making him the father of many nations.

Second, building upon the patriline of Genesis, God establishes an eternal covenant with Abraham, stating that he will be the father of many nations (Gen. 17:4–5). Most readers of Genesis, and many scholars, focus on the covenant of Genesis 15, which is about Abraham being the father of the one nation of Israel. However, the covenant of Genesis 17 is considerably more important and, subsuming the earlier covenant, extends Abraham’s fatherhood to the nations. This fatherhood is not biological in nature but spiritual. The covenant of circumcision guarantees that one of Abraham’s descendants will bring God’s blessing to those who acknowledge Him as their King. For this reason, the expectation of nations serving a future king is reflected in the patriarchal blessings given by Isaac to Jacob (Gen. 27:29) and by Jacob to Judah (Gen. 49:10). When we jump to the New Testament, we see that the Apostle Peter views Jesus Christ as the One who brings to fulfilment the promises given to Abraham (Acts 3:25–26). Similarly, according to the Apostle Paul, the promises associated with the covenant of circumcision are the basis for gentiles being included within God’s people (Gal. 3:15–29).

3. The theme of blessing is linked to the patriline that will eventually lead to Jesus Christ.

The third feature of Genesis that is frequently not appreciated is the way in which the theme of blessing is linked to the patriline that will eventually lead to Jesus Christ. In the garden of Eden, Adam and Eve’s actions result in divine curses that will negatively impact human existence. In marked contrast, God’s summons to Abraham offers the potential of divine blessing for all the families of the earth (Gen. 12:1–3). This theme of blessing is later associated with Abraham’s offspring (Gen. 22:18). While it is often assumed that this blessing will come through the nation of Israel as a whole, Genesis restricts the source of blessing to subsequent members of the patriline. This blessing (berakah) is linked to the person who has the birthright (bekorah). We see this especially in the story of Jacob and Esau, where Jacob is the one who brings blessing to others, a fact acknowledged by his uncle Laban (Gen. 30:27–30). In a similar fashion, Joseph is a source of blessing to others, a point made explicitly in Genesis 39:5 with regards to everything that Potiphar had “in house and field.” Subsequently, despite being imprisoned, Joseph is exalted to become “father to Pharaoh” (Gen. 45:8) and a source of blessing to various nations during a severe famine.

A wholistic reading of Genesis reveals that the book has been skillfully composed. As a literary collage, Genesis draws on different types of material to convey a unified message that importantly points forward to Jesus Christ, the source of divine blessing for all of us.

This article is part of the Every Book of the Bible: 3 Things to Know collection.